EKF vs. UKF performance and robustness comparison for nonlinear state estimation

Motivation⌗

The Kalman Filter (KF) estimates the state of a dynamic system based on noisy measurements, delivering optimal performance if the system is linear and noise is Gaussian. However, in real-world nonlinear systems, these conditions are rarely met. To address this, the community had proposed variations of the original KF that are sub-optimal but still provide good performance. Among the proposed solutions, two approaches have been widely adopted, the Extended-KF (EKF) and the Unscented-KF (UKF).

The EKF approximates nonlinear functions by linearizing them around the current estimate. In practice, due to complexity and computational cost, only the first-order Taylor series expansion term is used for the linearization. In contrast, the UKF estimates the mean and covariance of the state distribution by selecting a minimal set of points (sigma points) from the current state, propagating these points through the nonlinear system, and using the resulting transformed points to calculate the posterior mean and covariance.

As engineers facing a decision between these two, we seek insight into the following questions:

-

Which filter offers better overall performance?

-

Which filter is computationally cheaper?

-

Which filter is more robust to model mismatches?

This post explores each of these points by comparing the EKF and UKF in a simulated environment, assuming a target moving with Constant Turn Rate and Velocity (CTRV) and a sensor that measures range and bearing. Both the motion model and the measurement function are nonlinear, making this a perfect use case for comparing EKF and UKF.

Source code⌗

The source code for this post is avialable in the following Github repo: https://github.com/trujilloRJ/kf_sandbox

Table of Contents⌗

- Motion model and measurement function

- EKF and UKF algorithm

- Implementation

- Simulation and validation metrics

- Results

- Conclusions

- Appendix

Motion model and measurement function⌗

CTRV motion model⌗

We will consider a target moving on a 2D plane whose motion can be modeled with the CTRV. The filter state is represented in Fig. 1 and defined in polar coordinates as:

Where the subscript represents the time index and:

- and is the target position in the X and Y axis respectively,

- is the target heading with respect to X axis,

- is the target velocity along the direction of the heading,

- and is the target turn rate which represents the heading rate of change.

This motion model assumes that both the target velocity and turn rate are constant, the state transition function can be obtained as:

This function is clearly nonlinear, which means that if we assume the state distribution is Gaussian at time , passing it through this function will yield a distribution that is no longer Gaussian. This violates the assumptions of the standard KF, and using it here would lead to filter divergence. To address this, researchers have proposed various solutions, with the EKF being the most widely adopted in the industry. Implementing the EKF requires calculating Jacobians for the state transition function. For clarity and conciseness, these calculations are provided in the Appendix section.

Range and bearing measurement function⌗

As visible in Fig. 1, the sensor provides at each time the target position by measuring range and bearing defining the measurement vector:

However, the filter state contain the target position in cartesian coordinates. Therefore, to update it, we need a measurement function that maps between the state space and measurement space:

The measurement function is also nonlinear. The Jacobian of this function, required for the EKF, can also be found in the Appendix.

Modelling measurement and process noise⌗

Due to noise, the sensor never provides an exact measurement. The noise is usually modeled as independent random Gaussian distributions with zero mean and covariance defined as:

Where and represent the standard deviations of noise in range and bearing, respectively. These values are usually inherent to the sensor’s characteristics. For instance, in FMCW radars, range error relates to range resolution, which in turn depends on the waveform bandwidth.

Additionally, we must consider inaccuracies in our motion model, as real targets rarely follow an exact CTRV pattern. Variations due to maneuvers and slight path deviations are common. To account for this, we introduce process noise as zero-mean Gaussian distributions applied to the target’s velocity and turn rate . The covariance matrix is then calculated as follows:

where and

EKF and UKF algorithm⌗

EKF⌗

As previously mentioned, the EKF handles system nonlinearities by linearizing them around the current estimate. In practice, the main difference from the standard KF is that the matrices used for covariance propagation are the Jacobians of the state transition and measurement functions. The EKF cycle is represented by the following equations:

-

Prediction:

-

Update:

Where:

-

and are the Jacobian matrices of the state and measurement functions respectively,

-

is the innovation covariance,

-

is the Kalman gain,

-

and is the identity matrix for the dimension of the state, , in the specific case of CTRV.

An important note is that using the Jacobian, the EKF is aproximating the nonlinear function using only the first order term of the Taylor series expansion. Other, more accurate implementations of the EKF, incorporates second order terms but its implementation is unfeasible for most practical systems.

UKF⌗

The UKF tackles nonlinearity in a totally different way. Instead of trying to approximate the nonlinear system, it uses a method called the Unscented Transform (UT) to approximate the resulting probability distribution. This involves picking a set of special points, called sigma points, to represent the spread of possible states. These points are propagated through the nonlinear function, and from the results, the UKF estimates the new mean and covariance based on those transformed points.

Before diving into the UKF equations, it’s helpful to first understand the Unscented Transform. In this context, the UT can be defined as an operation that takes as input the state mean , covariance and the nonlinear function . Then, the UT estimates the mean and covariance of the resulting distribution after passing the state through the nonlinear function. In addition, the propagated sigma points are also of interest for UKF.

Step by step, the UT is doing the following:

1 Selecting parameters:

2 Computing weights

3 Generating sigma points set :

4 Propagating sigma points through nonlinear function (either or )

5 Estimating mean and covariance of the propagated distribution

Where is the dimension of the state and is the scaled square root of the state covariance matrix. The square root of a matrix is not defined, conventionally people use Cholesky factorization as an equivalent to matrix square root and that is what we used in the UKF implementation by leveraging scipy.linalg.cholesky function.

An excellent source to get intuition behind this and, in general, for KF is the book by Roger Labbe.

Finally, the UKF cyclic operation can be defined as:

- Prediction

- Update

It is important to remark that the UKF does not require the computation of Jacobians as opposed to EKF. Despite this, it has been proven that UKF is able to achieve approximations of 3rd order for gaussian cases.

Implementation⌗

The implementation of both filters is available in filters.py module. The EKF under EKF_CTRV class and the UKF under UKF_CTRV. The motion models and measurement functions are designed as dependencies, allowing for greater flexibility if different motion models or measurement functions need to be tested in the future.

A note on the CTRV implementation: in the transition function, the model becomes undefined when the target’s turn rate is zero . To handle these cases, the code simplifies both the transition function and its Jacobian to a Constant Velocity (CV) model.

Note on angle arithmetics⌗

Angles are modular quantities and as such, additional checks need to be in place when dealing with them. For instance, we cannot compute directly the average of a set of angles: the mean angle between 359 and 1 is 0, not 180. Instead, we need to use the circular mean to ensure accurate computations.

In our case, we have the bearing angle represented by in the measurements and the heading angle represented by in the state. It’s important to ensure that (i) these angles always fall within the range of , and (ii) we use the weighted circular mean when estimating the state mean in the UKF. The implementation for these is available in the filters.py module.

Note on UT parameter selection⌗

The selection of UT parameters and research field of its own with proposals ranging from the original paper by Julier to the scaled singma points by Merwe. Basically, these parameters controlled the spread of the sigma points around the mean which allow to approximate better (or not) the moments after nonlinear function.

However, another crucial aspect of parameter selection is its impact on numerical stability. For states with dimensions the first weights for the mean and covariance and become large and negative. This could lead to covariance matrices that are no longer positive definite which causes filter divergence. Therefore, the selection we adopted here is to avoid this and guarantee UKF numerical stability.

In fact, this topic has motivated an entire family of new nonlinear estimation filters. The Cubature Kalman Filter (CKF) operates under the same principle as UKF but employs the cubature transformation to generate the sigma points, ensuring numerical stability.

Simulation and validation metrics⌗

A simulated target is generated to move in a straight line at a constant velocity, followed by a sharp turn, and then resumes straight-line motion. A sensor continuously provides noisy measurements of the target’s range and bearing at each frame. Below is a table summarizing the parameters used for the simulation, including details about the sensor errors:

| Parameter | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Time between frames | 200 ms | |

| Iterations | 10 | |

| Sensor range standard deviation | 0.5 m | |

| Sensor azimuth standard deviation | 2 | |

| Process noise velocity | 1 m/s | |

| Process noise turn rate | 3 |

All the simulation logic is contained in the simulation.py module. The figure below illustrates an example of one iteration. It’s important to note how the position errors in the X and Y coordinates increase as the target moves further away from the sensor. This behavior is expected, given the nonlinear nature of the conversion from polar to Cartesian coordinates.

The metric selected to evaluate the performance of the filters is the classical Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) defined as:

Where is the number of iterations, is the filter estimation at the i-th iteration and is the true value.

Results⌗

The entire code for the validation, including figures, can be found in the notebook ekf_vs_ukf.ipynb. The following figure shows the estimated state at each frame averaged by the number of iterations.

As seen in the results, the EKF initially demonstrates faster convergence, particularly for velocity estimation. However, when the target begins its turning maneuver, both filters struggle to keep up with the true position and turn rate estimations. This lag is anticipated because the CTRV motion model does not account for changes in turn rate.

Notably, the UKF exhibits better performance during the turn; although its turn rate estimation is still somewhat delayed, it does not overshoot as significantly as the EKF. This characteristic results in a lower root mean square error (RMSE) for position estimation, as will be illustrated in the following figure.

As designers, we can enhance the performance of both filters by increasing the process noise ( q_w ). However, this adjustment comes with a trade-off, as it may lead to less accurate state estimations during periods when the target is moving in a straight line. Choosing appropriate values for the process noise is a topic worthy of its own post—perhaps something to explore in the future! 😉

To further illustrate our findings, the following figure displays the root mean square error (RMSE) over time for position (combining X and Y), heading, velocity, and turn rate.

First, let’s focus on the position RMSE. In practice, this is the most important metric, since a big error in position could lead to misassociation and track loss which is critical for many applications. Overall, both filters offer better position estimation that what the raw measurements provide. Obviously, this is expected and one of the advantages of using a KF for state estimation.

However, at the beginning of the target’s turn, there is a brief period where both filters exhibit higher position RMSE than the measurements. This occurs due to filter lag caused by the target’s maneuvers, which are not accounted for in the motion model. Among the two filters, the EKF performs the worst during this phase, as its RMSE peak is higher.

Additionally, the UKF outperforms the EKF in estimating the target’s heading during the turning maneuver, consistently maintaining an RMSE below ( 10 \degree ). The same trend is observed for turn rate estimation, where the UKF shows superior performance. Conversely, the EKF demonstrates better estimation of target velocity during the maneuver compared to the UKF.

Just for the purpose of illustration, this GIF provides a zoomed view of the behaviours of both filters during target turning. The effect of lagging and later overshoot is visible for the EKF.

Robustnes to process noise mismatch⌗

For real applications, selecting the proper process noise is a challenging task. Filter designers must consider all potential maneuvers and movement patterns of the target. For instance, in automotive applications, a vehicle can brake, turn, cut in, and more. Additionally, motorcycles are likely to perform more maneuvers than cars.

This selection process requires careful validation using extensive amounts of real, labeled data collected across various open road scenarios, as well as in simulated and controlled environments. Unfortunately, such data is often not readily available, leading to suboptimal process noise selections in many cases. Therefore, it is crucial to test the robustness of the filters against process noise mismatches to ensure reliable performance in real-world situations.

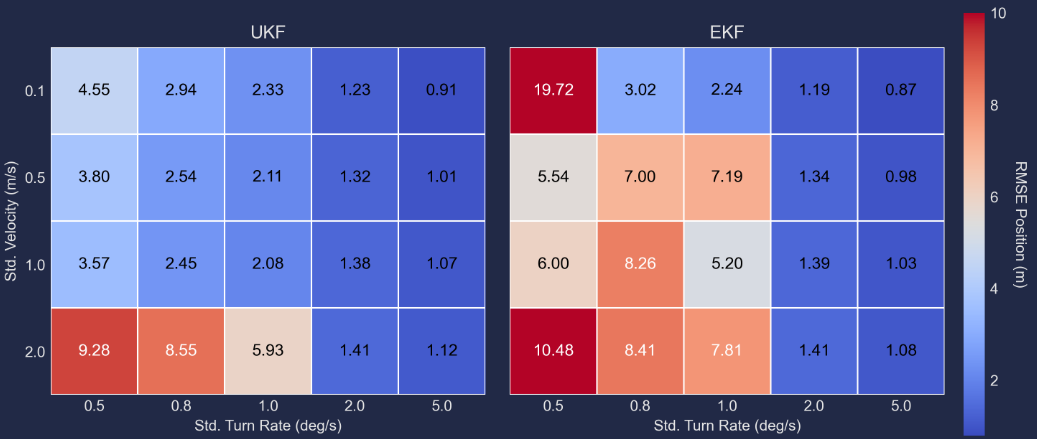

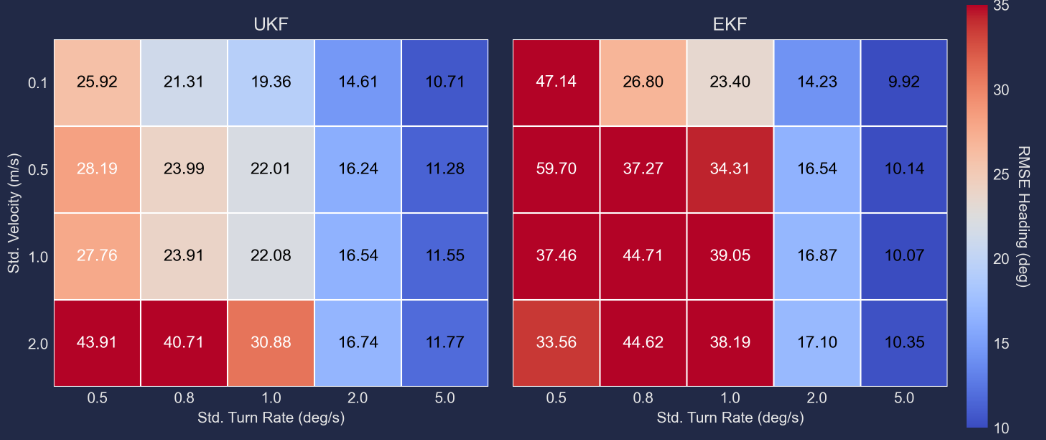

To perform this task, in the notebook ekf_vs_ukf_robust_test.ipynb, we have measured the RMSE of the filter estimations in 10 iterations with 4 different values for and 5 for for a total of 20 process noise combinations.

The following heatmaps show the averaged RMSE over iterations and time obtained for each filter using a given process noise combination. One key observation is that has a more significant impact on performance than . Notably, both filters demonstrate their worst performance when . This is expected, as this value fails to adequately capture the maneuvers performed by the target. Despite this, the UKF maintains significantly better position estimation than the EKF under these extreme conditions.

In general, the UKF seems to be more robust to mismatches in process noise, starting from the position RMSE is reasonable and much lower than EKF for the same value of process noise. This conclusion is also valid for the heading estimation.

However, the EKF can achieve comparable, and in some cases slightly better, performance than the UKF when the process noise values are appropriately chosen. This improved performance, though, comes at the expense of greater sensitivity to mismatches. Consequently, if the EKF is the chosen filter, designers must devote considerable attention and resources to selecting the process noise carefully to ensure optimal performance.

Computational cost⌗

The computational cost was measured in terms of time of execution per frame for each filter. A simple validation was conducted using time.perf_counter_ns from Python time module on each iteration and frame and later on reporting the average time per execution for each filter.

| Filter | Average time per frame (ms) |

|---|---|

| EKF | 100 us |

| UKF | 620 us |

The reported values are not particularly relevant in absolute terms, as they can vary significantly based on the hardware platform and the programming language used for implementation. However, in relative terms, the results are noteworthy. Specifically, the EKF is approximately 6x faster than the UKF when using the CTRV model with range and bearing measurement functions. This difference is especially important in scenarios where the implementation is aimed at embedded environments with limited computational resources.

As a word of caution, I cannot guarantee that my implementation is the fastest for UKF and EKF. Optimizing for speed was not the primary focus of this experiment. However, I made an effort to vectorize as many operations as possible by leveraging the functionality of the numpy library.

Conclusions⌗

The UKF and EKF were implemented using CTRV motion model and tested in a simulated environment with a sensor providing range and bearing. The results lead to the following conclusions:

-

When desing properly, both EKF and UKF are effective solutions for nonlinear filtering, offering similar performance.

-

The UKF is more robust to process noise mismatch than the EKF, making it preferable for applications characterized by a high degree of uncertainty where robustness is critical.

-

The EKF is computationally cheaper than UKF, which can be a significant advantage for applications that need to run in resource-constrained environments.

-

A hidden advantage of the UKF over the EKF is that it does not require the computation of Jacobians. While this is not a major concern for this experiment—since both the measurement and transition functions are analytically derivable—this could be a significant advantage in more complex scenarios where Jacobians are difficult or impractical to compute.

Future steps and remaining questions⌗

It is important to remark that this evaluation and comparison is by no means exhaustive. A logical next step would be to test additional scenarios, such as what happens when the velocity changes. For instance, how would the filters perform if we introduce tangential acceleration to the target?

Also, these conclusions cannot extrapolated completely to other applications. The performance of each filter is influenced by the specific nature of the nonlinear functions involved. Other factors, such as the time between frames and the intensity of measurement noise, also contribute to variations in filter performance, leading to different outcomes.

A natural next step will be to incorporate Doppler velocity into the measurement function, since radar sensor are able to measure this value. This addition would make the measurement function even more nonlinear, potentially altering the performance of the filters. Exploring these variations will provide deeper insights into the capabilities and limitations of both the EKF and UKF in diverse situations.

On the same idea, it could be interesting to extend the motion model to Constant Turn Rate and Acceleration (CTRA). This more complex motion model can simultaneously capture both acceleration and turning maneuvers, providing a more realistic representation of target behavior in dynamic environments. By implementing the CTRA model, we could assess how well the EKF and UKF adapt to more intricate scenarios, potentially revealing additional strengths and weaknesses of each filter.

Please contact me via Github if you have any suggestions or want to see any of these steps developed 😊

Appendix⌗

1- Jacobian of the transition function:

2- Jacobian of the measurement function: